How did all the talk of NBA expansion leave Mexico behind?

MEXICO CITY — For decades, talk of an NBA franchise in Mexico was not fringe speculation but a recurring thought experiment in league discourse, especially as the league deepened its ties with Mexican basketball fans and infrastructure as years passed.

The NBA first staged an international game on Mexican soil back in 1992 — its third-ever matchup outside of the United States — when the Dallas Mavericks and the Houston Rockets faced each other at Palacio de los Deportes in Mexico City. So great was the experience that the league sent the Rockets and, this time, the New York Knicks for another preseason matchup one year later.

Ultimately, Mexico went on to put together a five-year run of hosting exhibition games for the NBA, then welcomed American teams sparsely in 1999, 2000, 2003, 2006, 2009, 2010, and 2012. The first regular-season NBA game to take place in Mexico happened in 1997, and the south-of-the-border country has hosted such games every season since the 2014-15 one, barring the COVID-impacted campaigns.

The arrival of the CDMX Capitanes to the G League only intensified the Mexican belief of belonging, giving fans their closest link yet to the NBA when they joined the NBA’s developmental league in 2021-22 after they were officially welcomed two years earlier, in 2019.

And for a major segment of those supporters — call them dreamers, idealists, or any other optimistic descriptor you can find for them — the ones convinced that an NBA franchise belongs here almost by birthright, the expectation now feels like set-in-stone destiny rather than a mere, perhaps even distant, possibility.

Those fans talk about expansion not as a remote outcome, but as something that could, or for some, should, happen as early as “tomorrow.” In their minds, the city formerly known as Distrito Federal and politically rebranded into — coincidentally or not — much more internationalized CDMX is huge, vibrant, full of passionate fans, and simply the right place for the NBA to land next.

“Mexican fans bring more passion than people think,” said a supporter named Alex, pointing to how soccer culture has translated naturally into basketball fandom.

At different points in time, during press conferences tied to NBA Global Games in Mexico City, commissioner Adam Silver publicly described the city as a potential site for future expansion.

“We think there’s an enormous opportunity to continue growing the game of basketball here in Mexico City and throughout the country,” Silver said in Nov. 2023. “And we also see this as a gateway essentially to the rest of Latin America.”

But even at the height of that buzz, the conversation was not one of imminent commitment to expanding south of the American border. By late 2024, Silver was clear that Mexico City’s place in expansion was still behind compelling proposals from other American markets.

“Personally, I would love to have a team [in CDMX],” Silver said then. “[But it] would be more difficult to expand to Mexico City than it would be to expand to U.S. cities that have very publicly sought NBA teams.

“Being direct, it’s highly unlikely Mexico City would jump above U.S. cities that are currently under consideration.”

Capitanes, for one, keep proving Silver right (in making a strong case as a proper fit for NBA expansion) and wrong (as a team based in a place still far from being an NBA-level hub).

The team’s games take place in cavernous Arena CDMX (opened in 2012 and with a maximum capacity of 22,300) and are packed with families, fans pounding drums, Latin American flags representing the multinational talent showcased on the court, and a level of emotional attachment that does not exist anywhere else in the G League.

Many Capitanes supporters attending the team’s home opener for the 2025-26 season against the OKC Blue insist the city is ready for the NBA in every way that matters: culture, passion, atmosphere, and symbolic weight. They describe Capitanes games as proof that Mexico City can be a “basketball destination,” a place where fan noise, family crowds, and a growing sense of belonging are enough to convince the league to plant a flag here permanently.

“Mexico City is ready,” claimed a middle-aged fan named Adrian. “With the team we have, any players would adapt to it tomorrow.” For him and many others, the city’s size, diversity, and infrastructure already solve everything the NBA or outsiders might be worrying about.

“The atmosphere here is special,” said Leo, a longtime fan who attended the opener along with his wife and three kids. “People feel connected to the team. It’s a family thing, and the fans give everything. We already support this like an NBA team.”

The CDMX team steadily leads the league in attendance, and although it took some ruthless and conniving marketing related to LeBron James’ son Bronny to break the all-time record, they destroyed the prior mark — one that already belonged to them — by bringing 19,328 souls to the arena for a developmental-league game held on Jan. 4, 2025 (that ended up not featuring Bronny after all).

Capitanes’ jerseys and all other merchandise sales are unparalleled, and the social engagement the team generates is on another level. They are the only unaffiliated G League team after the Ignite project vanished, but that fact only helped Ciudad de Mexico Capitanes feel like a true national project.

On the surface, one could believe Capitanes simply has outgrown and outpaced the G League structure. It feels like a leap from a player-development league and its surroundings to a full-blown competition, such as the NBA, is the most natural of moves. So much so, that a Capitanes PR member just confirmed tickets for international NBA games staged in CDMX always fly off of selling platforms the minute they go up for sale.

To many fans, the conclusion is simple: if Mexico City can fill the building for a one-off game in the middle of the NBA season, it can fill it 41 times a year with a local team calling Arena CDMX home.

But the closer the NBA gets to defining its future, the clearer it becomes that Mexico City’s biggest obstacles are not emotional or cultural. They have everything to do with infrastructural and financial hurdles, and they are, inevitably, deeply tied to the Association’s global strategy.

People who work inside Capitanes — the staffers, the media members who cover them daily, the executives who deal with the League (NBA or G) on a daily basis, and even the most fervent of super-fans who have earned unique access to all things Capitanes and call themselves Familia Capitan, understand the scale of these challenges far better than the dreamy fans who can only imagine a seamless transition into the largest stages basketball has to offer.

For some around the organization, the idea of a near-term NBA franchise is outright impossible to entertain.

“No,” Capitanes PR staffer Raúl Bravo told SB Nation when asked whether an NBA expansion could happen in the short term. “There are a few reasons. There’s competition from other cities like Las Vegas and Seattle. And even if the NBA called us and said ‘let’s go,’ the financial power needed to operate an NBA team is enormous — more games, more hotels, more staff, more everything.

“NBA player salaries are way above those of the G League players, so the investment would be magnified incredibly, and out of reach.”

The most common thread among insiders navigates the understanding that, beneath the NBA-level arena and the international buzz generated by the team and their approach to roster building in what most consider “the team of Latin America,” Capitanes operate on a reality completely different from what an NBA franchise requires.

When Bravo describes the problem, he is not talking about the fanbase or the Mexican culture being roadblocks on CDMX’s path to the NBA. Bravo is talking about the organization-wide budgets, high-end salaries, top-tier facilities, and fine-tuned logistics needed to be in place in order to make the jump. The gap in all of those areas, sadly, cannot be closed by the immeasurable passion and the emotional pull of Capitanes.

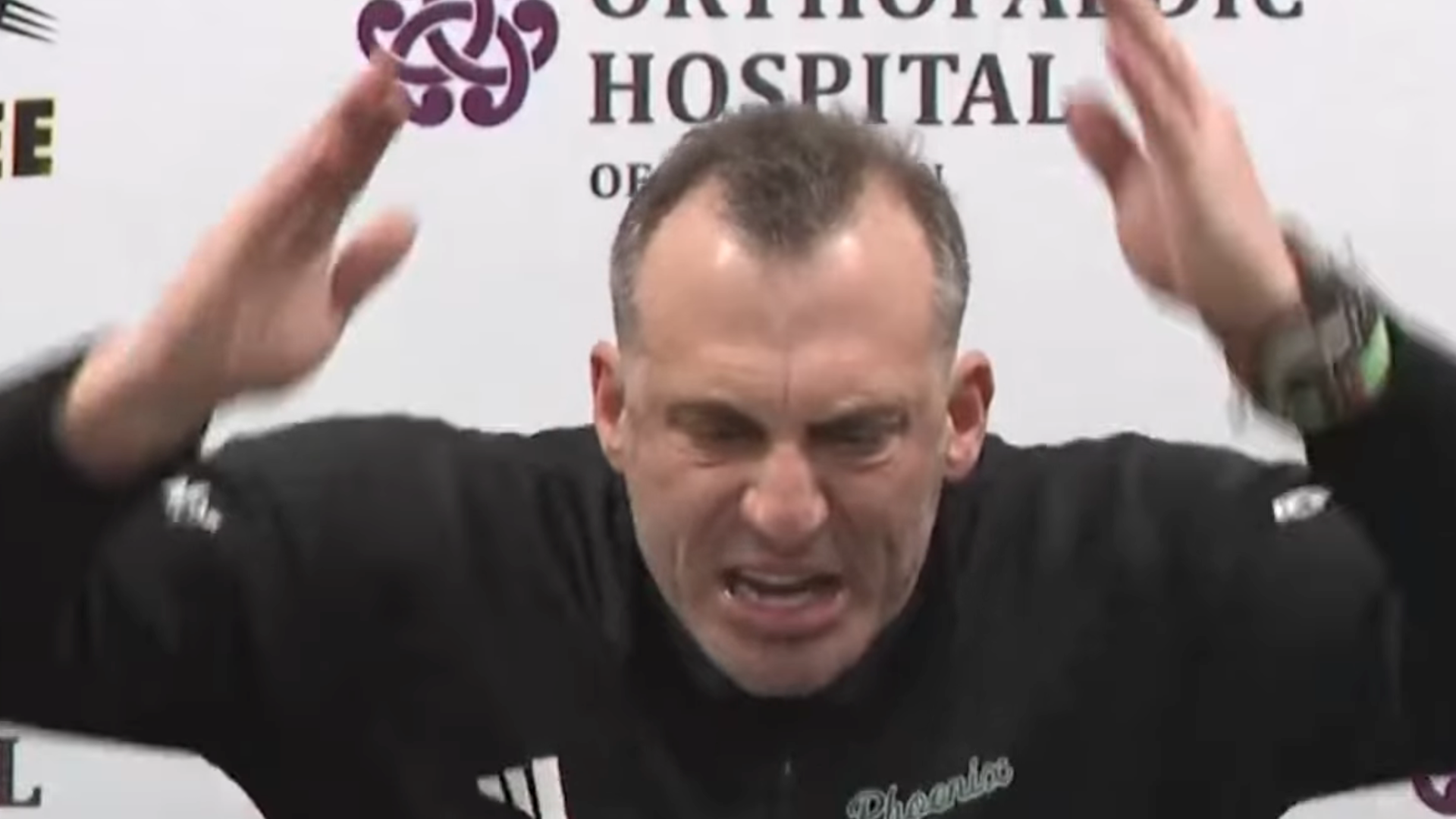

Capitanes head coach Vítor Galbani, in his first season at the helm, framed the gap directly when discussing the day-to-day competitive realities the team faces shortly after earning his first win of the season, in front of the Arena CDMX crowd.

“We have fewer resources than other teams,” Galbani said. “We’re at the mercy of call-ups. Other teams can send NBA players down and bring them back up. We can’t. Our roster is built differently — younger, mostly Latin American — and that makes the challenge bigger.”

Galbani’s view also speaks to a deeper truth that fans still don’t quite grasp: Capitanes are designed as a development platform, not a contender, as independent as they might be.

From the fans’ perspective, there’s a powerful emotional component at play that trumps it all, given the fact — acknowledged and proudly communicated by the organization itself — that Capitanes represents not just Mexico City, but the whole Latin American landscape.

The feeling, which extends well beyond Mexico’s borders, is what makes Capitanes what it is and has always been, and in the eyes and hearts of most fans, it’s not going anywhere — expansion or not.

“Capitanes, even if they’re not full of Mexicans, represent Latin Americans,” said Gerardo, a fan whose kid is honing his skills at the Capitanes’ underage developmental team. “It’s a platform for the player who wants to reach the NBA and sees Capitanes as a trampoline.”

The Latin American identity of the team is a core branding element, a selling point for fans, and a genuine pipeline for players with dreams of making it to the NBA or hooping overseas. But if the Capitanes were ever to become an NBA franchise, that identity would disappear almost instantly.

One staff member stated clearly: “There’s no way to keep five Latinos on an NBA roster — the level isn’t there.”

“That core wouldn’t survive,” said Rubén Calderón, who works both for Capitanes PR and NBA Mexico. “It’s impossible. Fans don’t see it — maybe because they don’t understand how the NBA works — but you can’t have five or six Latin American players on an NBA roster unless they’re truly NBA-level.

“There’s not enough Mexican and Latin American talent to keep an NBA team competitive.”

A fellow Capitanes PR member echoed that sentiment: “People don’t see that. Maybe because they don’t really know the NBA level.”

The human contradiction is as obvious as it is disheartening. Capitanes fans love the team for the most part because it represents them, from cultural traits to the region, starting in the northernmost Baja California and spanning all the way down south to Chile’s Magallanes y la Antártica Chilena Region.

“People from Latin American countries — Brazil, Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico — they’re not going to fly to the NBA to watch a random game,” says Capitanes superfan Sinuhe Yepez. “But they’d come here and pack the arena to root for their colleagues and to watch teams that come from the United States.

“They’d be paying a fifth of the cost in CDMX compared to attending a game in the USA, and they’d get the same experience.”

An NBA franchise built in Mexico City would not represent that at all. The Association tipped off in October with a record 135 international players from 43 different countries across six continents.

The Atlanta Hawks, with 10 international players, led the league on that front. None of them was born south of the United States of America.

Multiple media members, including national reporters Erick Aguirre and Mario Alberto Castro, brought this up immediately.

“There would be a loss of identity,” they said. Both agreed that a roster built on Americans, as any NBA roster has its foundation in, would change the heart of what Capitanes currently are.

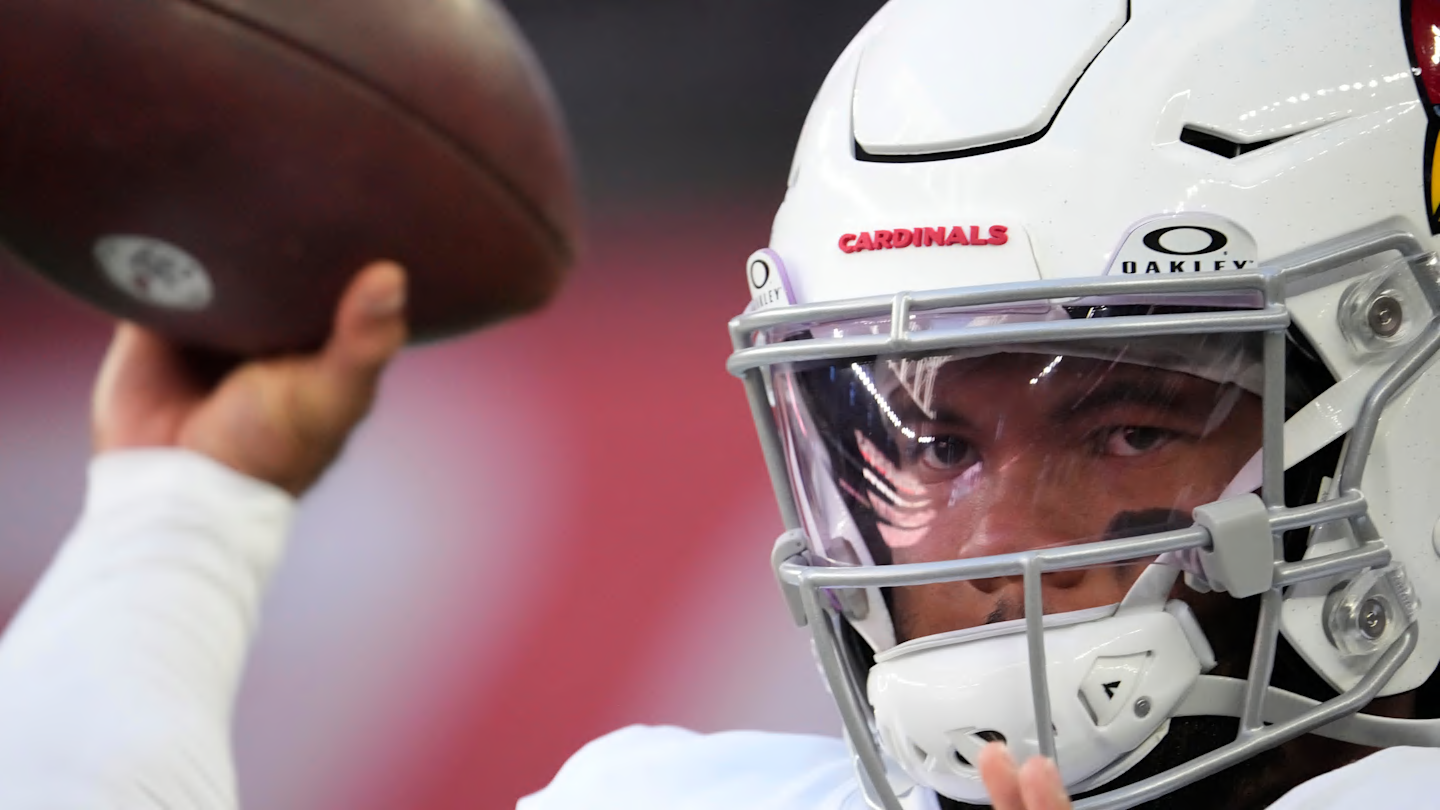

“You need a Latin icon,” they argued. “A Jaime Jaquez Jr. or a Juan Toscano Anderson. Ideally, someone like [NBA prospect] Karim López.” Without that, they fear fans would lose their rooting anchor and thus their interest in attending Capitanes games and following the team so closely and passionately as they currently do.

None of the conversations above, however, addresses the largest barrier of all: the humongous financial effort needed to make it to the NBA.

Every person inside the organization who deals with logistics on a weekly basis mentioned the facilities problem currently hurting CDMX’s case for landing an expansion team.

“To have an NBA franchise, you need a place where the entire team — offices, staff, medical, athletes — can spend their time and operate,” Calderón said. “Capitanes don’t have that. They train at the Comité Olímpico Mexicano (around 6.5 miles from Arena CDMX). Offices are split into COM and a separate building in the southern part of the city. Capitanes don’t own the arena, and everything is scattered.”

More worryingly, a few staffers revealed that there is nowhere in the city to build centralized facilities akin to what the NBA would require, or at the very least prefer.

“In the Valle de México area, there is no land left of that size,” Calderón said. “Not with the location needed. Around the arena, there’s nothing — you can find train yards, old neighborhoods, and then the poshest in Polanco. But there’s no open space.

“To build such facilities, you would need to build a new arena with everything in one place, and that means finding land far away from the current location and the city center — let alone the massive investment and the amount of money that’d take.”

It is a view echoed by people who see the team every day, such as Rodrigo Goyeneche, one of Mexico’s most reputed up-and-coming media voices and a longtime analyst for both Capitanes and fellow CDMX basketball team Diablos Rojos of Mexico’s Liga Nacional de Baloncesto Profesional.

“Being fully honest, right now, we’re not ready for something like that,” Goyeneche said. “Not structurally, not logistically. The arena is huge, but the NBA needs more exclusivity. And here, the arena is privately owned and used for concerts and many other events. It’s not built for hosting a team every other day.”

The “exclusivity” of becoming the freshest member of the NBA family would inevitably bring a larger expense with it. Many supporters attend Capitanes games, and surely all of them adore the NBA Mexico Game, but they don’t attend it because it’s cheap — they attend because it happens just once a year.

Tickets for this season’s Mavericks vs. Pistons game on Dia de Muertos ranged from 850 pesos (around $46 USD ) to nearly 20,000 (approaching $1,090 USD), sitting courtside. Capitanes’ G League games are affordable, with the cheapest tickets available for 50 pesos (less than $3 USD). For a single event, people save, plan, and spend. But a season of 41 home games at that rate, the equation would change entirely.

“A lot of fans struggle to get to the arena,” one Capitanes staff member acknowledged. “They only come on weekends. Between weekday and weekend sales, the difference is huge.”

Local fans who save for months to attend a single NBA Mexico game, or who buy Capitanes jerseys knowing the player may leave next month, would suddenly face a season with 41 home games and consistently NBA-level prices. Most of them simply could not afford NBA prices or frequency. Yepez, one of the most passionate and active fans of Capitanes, acknowledged he’s stopped attending so many games already for financial reasons and an increase in prices.

“I need to earn a lot of money to afford attending,” Yepez said. “Back then, I got full-season tickets close to courtise for 7,000 pesos. Now, I need to pay close to 2,500 pesos per game to sit in the same area. I’d probably need to sell an eye and a kidney to afford that.”

Goyeneche also pointed out the competitive reality that many fans often overlook when rooting for their home team, which has to do with the developmental nature of the G League compared to the NBA.

“The goal now isn’t to win a championship,” Goyeneche said. “It’s to develop talent. But people want a champion. They want their stars to stay. And with Capitanes, the roster changes every year. Yet the fans still come. That’s unique, but it has everything to do with the core values of the organization.”

While fans would get more familiar with the team’s faces and supposedly know Arena CDMX like the back of their hands, would they be able to pony up the money needed to root for their squad at the court level three times a week?

That tension is reflected in talking with fans who follow the team closely but acknowledge the financial limits already in place while being part of the lesser, more affordable G League.

Ivan, a longtime Capitanes and Oklahoma City Thunder fan, envisions the dream clearly but understands the barrier.

“There’s still not a big enough basketball fan base in Mexico for the NBA to give the country its own team,” Ivan said. “Capitanes helped grow the fanbase. More people follow the sport now, but there’s a long way to go.”

For Ivan and many others, travel is another point to consider. Flying from Mexico City to Texas doesn’t pose a big challenge. Flights to Cleveland or Toronto, in Ivan’s eyes and pocket, are long and costly.

From a logistics standpoint, the NBA solved the concern years ago. While it’s been proven that travel isn’t an operational barrier these days, for franchise ownership, staff, and operations, the expenses related to it could become unmanageable quickly.

And that is exactly why NBA discourse has pivoted heavily toward planting a flag in Europe rather than exploring home expansion, let alone looking south of the border.

Although Silver said after September’s Board of Governors meeting that the league was on “parallel tracks” regarding potential expansion involving both national and international moves, things appear to have changed of late.

While there has been resurgent buzz about Las Vegas and Seattle in recent weeks, over the past few months, the league has signaled that its most urgent expansion opportunity is not in Mexico or the U.S., but across the Atlantic. The “NBA Europe” project, tentatively targeted for a 2027-28 proper launch, would include up to 16 teams in cities like London, Paris, Berlin, Rome, Milan, Madrid, Barcelona, Athens, and Istanbul. Then, in late December, both the NBA and FIBA made their “joint exploration” of a new league based in Europe official.

The NBA has already hired JPMorgan Chase and The Raine Group to secure investors. The conversations, according to multiple reports, have involved sovereign wealth funds, private equity firms, and ultra-wealthy family groups. The Middle East has shown particular interest, given that it could finally find a way to circumvent the current rules capping foreign passive ownership at 20 percent in NBA teams.

What Europe offers is simple: enormous capital, established sports corporations arriving from the soccer sphere, existing arenas already owned by world-renowned organizations such as Real Madrid, Barcelona, and Bayern Munich, massive markets with a foothold in the continent’s premier competition — the Euroleague — and global investment appetite to tie their names to the NBA.

According to the NBA’s Managing Director for Europe and the Middle East, the NBA sees a “$50 billion European sports market” and noted that basketball barely captures “0.5 percent of it.” Not to mention, some NBA owners — most notably Knicks steward James Dolan, according to rumors — are hesitant to dilute U.S. media revenue further unless expansion fees are astronomical, while the European model would offer them a parallel revenue stream with no media dilution at all.

None of these incentives points toward Mexico City landing a team for the time being.

The immediate implications of the European move are unmistakable. If the NBA arrives in Europe by 2028, the move could delay U.S. expansion for years. And if ownership groups with the deepest of pockets push billions into the project, Ciudad de México will inevitably slip further away — not because it lacks passion, but because the NBA’s financial thirst will lie elsewhere.

Even the most optimistic insiders acknowledge the financial gap. NBA Mexico managing director Raúl Zárraga, speaking before the 2024 NBA Mexico Game, praised Capitanes’ success in building a collective Mexican and, by extension, Latin American identity.

“When you are in the arena, you’ll see that the people are rooting not for Mexico City Capitanes, they’re rooting for Mexico’s Capitanes,” Zárraga said.

He also praised their competitiveness, merchandise leadership, and visibility throughout multiple channels. But even Zárraga, with at least some partial, inside knowledge of the NBA’s operations, offered no timeline for NBA expansion into Mexico.

“There’s no plan in action to look for a potential owner or potential group of people dedicated to get a new team in Mexico or in any other place in Latin America,” Zárraga said. “So there’s nothing new to announce or confirm about Mexico being considered.

“It’s a complicated process. You can imagine the international locations, all the different cities, but there is no doubt that many cities will be participating, including Mexico City.”

In the sharpest corners and deepest streets of Ciudad de México, the people closest to the Capitanes project understand that better than anyone. When asked whether an NBA roster could adapt to living in Mexico full-time, staff members repeatedly said yes — but with caveats.

Calderón said players would “live in good zones, with a good quality of life,” as they do now as members of the G League squad. That said, he cautioned they’d effectively be forced to live in a bubble, having personal chefs, security, private routes, and minimal city interaction.

Others mentioned that Capitanes already house players in the Polanco neighborhood, one of the most expensive areas in Latin America, hosting the most expensive street in Mexico, and believe that the model could scale to host a full NBA operation.

Idealistic Capitanes fans, meanwhile, don’t deny the challenges; they simply believe everything will sort itself out. Cultural adaptation? “They will adapt.” Travel? “Distances aren’t worse than some NBA-to-NBA trips.” Roster identity? “Capitanes represents Latin America.” Financial strain? “It’s the NBA — they’ll make it work.” Player discomfort? “They’ll live in Polanco.”

These solutions, however, highlight another gap. For an NBA franchise, such bubbles must be permanent, secure, and supported by a full organizational machine, bringing back to the table one more financial hurdle to clear and invest in.

Even the city’s biggest strengths, like Arena CDMX’s size and ambience, come with their own challenges. Bravo pointed out that weeknight attendance is a problem already in the G League.

Some fans, who attend games clad in bootleg clothes available for purchase at pirate-market prices — snapback hats at 100 pesos or $5 USD, and screen-printed jerseys selling at 150 pesos or barely $9 USD — right outside the stadium, admitted that Capitanes games scheduled on working days noticeably have “less atmosphere.”

Going from barely 20 home games to double that figure if in the NBA is an entirely different sales reality.

A longtime superfan from Europe, but who has lived in CDMX for a few years, put the economic tension bluntly. “Tickets for the annual NBA game can cost 20,000 pesos courtside,” he said. “Capitanes’ games remain accessible, but an NBA season? Only if the NBA puts in money to help the organization. With a single owner here, it’s difficult.”

Across interviews, one underlying thread emerged from insiders, journalists, and staff, in that they all agree about the collective desire to keep Capitanes grounded in what they currently are — not an NBA team, but a gateway to the League.

A development hub for Latin American talent, a cultural point of pride, a bridge between the NBA and a region that hungers for representation in the biggest stages, and is eager to announce itself to the world. A team whose power comes from being different, not similar.

And ironically, that difference is exactly what would disappear in the jump to the NBA.

The players would be mostly from United States towns and come with American upbringings. The structure of the organization would be more centralized, the roster rules won’t allow Capitanes to rotate the cast of Latin talents, the operations would be much more strict, and the culture and atmosphere risk getting under heavy control and within stiff boundaries.

One fan admitted he fears the NBA would water down the true Mexican spirit that currently exists in the arena for a more Americanized audience, and risk the loss of Spanish chants, the charming presence of team mascot Juanjolote and other sponsor-affiliated wild characters, the cameos of paper-built Alebrijes, and the use of other local traditions, tunes, or Mexican descriptions of what’s going on on the court, from coaches’ challenging plays, to (Silencio! Sshhhhh…) tense moments at the free-throw line.

Asked if expansion could maintain the team’s Latin American identity, a fan named Roberto paused before offering his most honest answer.

“It would hurt a little,” he said. “It’d take away part of the fanbase.”

The drums? Might be muted. The Spanish chants? Curated. The fans who love the chaos and identity that make Capitanes a unique entity in the world of basketball would face a polished entertainment product built for global, if not American, consumption.

The people who work inside the organization know this truth intimately. They also know Mexico City is not ready. Not because it lacks heart, but because it lacks the dollars, acres of land, modern NBA facilities, an owner willing — and capable —to fund a multi-billion-dollar project, and a league that sees Europe as a more strategic and profitable next step.

So while Mexico City is closer to the NBA than ever before in history, the NBA, however, is moving somewhere else in its global strategy.

Capitanes may have already proven that Mexico is a basketball country. They have proven that the fans will come to the games, fill the arena with deafening noise, and build a culture that can sustain the sport. What CDMX cannot prove is that the infrastructure exists to support the most powerful league in the world and the business of the NBA — at least not yet.

Until that gap closes, the vision remains what it has always been: an emotion-fueled dream, just out of reach.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0